It was the sixth day since a peaceful sit-in had begun in Gezi Park in Istanbul to protect the last remaining green space in the center of the city. Protests had spread throughout the country due to the excessive use of force by police, including tear gas, water cannons, and plastic bullets against protesters from various backgrounds. On this same day, 2 June, Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan gave a talk on the importance of preserving the Ottoman heritage at the opening ceremony of the new facility for the Prime Ministry’s Ottoman Archives in Istanbul. The contrast between the contents of the building and the content of Erdoğan’s speech was startling. Besides stating the importance and the richness of the archives, holding almost ninety-six million documents and three hundred and seventy thousand register books that date back to Fatih Sultan Mehmed’s era, Erdoğan’s speech was predominantly on the protests in Taksim. Erdoğan declared: "I am not the master of the people. Dictatorship does not run in my blood or in my character. I am the servant of the people."

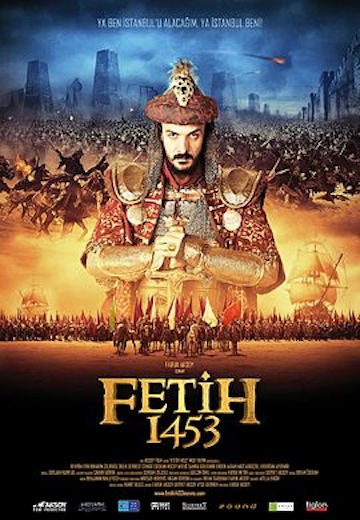

In the last ten years, people in Turkey have shown increasing interest in historical dramas, historical novels, and live broadcasts of discussions of the history of the Ottoman Empire. Muhteşem Yüzyıl [Magnificent Century], a massively successful Turkish soap opera set in the golden age of the empire that dramatizes the intrigues of Suleiman the Magnificent’s harem and court, has also become popular in the Balkans and in many countries of the Middle East. In 2012, Erdoğan said about the show: “That’s not the Sultan Suleiman we know, that’s not the Lawgiver we know; thirty years of his life was spent on horseback, not in a palace like you see in TV shows.” Erdoğan condemned the director of the series and the owner of the television station airing the show, claiming that the series distorted Ottoman history and the image of the great sultan. He also called on the judiciary to take action against the show. In the same year, Fetih 1453 [The Conquest 1453], a Turkish epic film with an 18.2 million dollar budget based on the story of Mehmed II’s capture of the old Byzantine capital Constantinople, broke box office records in Turkey.

But even as the public sphere was filling up with these new discourses of the “glorious” past, journalists who tried to report on and argue against present political practices were being silenced by criminal charges, trials, and imprisonments.

[Poster for Fetih 1453 (Conquest 1453).]

The political agenda and rhetoric of the ruling Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi [AKP] has been fed by this “Ottomanalgia”: a carefully constructed nostalgia for the “glorious” Ottoman past. Ottomanalgia encompasses a series of attempts to “Turkify” Ottoman history, such as calling Ottoman sultans Turkish notables (Türk Büyükleri). It also aims to strengthen the so-called “historical” connections between the “golden ages” of the empire and the current economically rising star of Turkey. Its proponents praise Ottoman imperial co-existence as Muslim “tolerance,” rather than as the imperial pragmatism of population management and taxation policies that were practiced by most successful empires throughout history. This tolerance discourse repeatedly makes references to the Jews welcomed to Ottoman territory after the expulsion from Spain and Portugal in the late fifteenth century, and refers to Armenians as the “loyal nation” (millet-i sadıka), in order to emphasize the multicultural coexistence of the empire. Both references contain large grains of truth. Ultimately, however, Ottomanalgia is a wild misreading of the past, intended to cover and justify what is going on in the present: the creation of an atmosphere of intolerance towards dissent, religious difference, and—most patently to the protestors’ many supporters—towards different lifestyles in contemporary Turkey.

Ottomanalgia is not limited to Erdoğan’s speeches and interviews. It can also be seen in the new building projects and the “Ottomanization” of public spaces and government buildings in Istanbul. The city is being turned into a series of political statements in an ongoing attempt to create a new, Islamist national memory through redesigning the urban landscape of contemporary Istanbul.

[Miniature of Topkapı Palace in Miniatürk. Image via Wikimedia Commons.]

The proposed erasure of Gezi Park and the lively chaos of Taksim Square to construct a symmetrical, easily monitored mall like Demirören, full of homogenized international consumer goods, is what has been receiving attention since the protests began. But there are several other examples of this Ottomanization of public spaces. At Miniatürk, opened in 2003 as one of the world’s largest miniature parks, Ottoman history is turned into tiny, simple, and easily digestible morsels of national pride, without any actual, complicated human beings in the frame. In 2009, Erdoğan opened the Panorama 1453 History Museum, dedicated to the conquest of Constantinople, in Topkapı. The museum is a monumental three-hundred-and-sixty-degree painting depicting Ottoman soldiers on the battlefield, accompanied by 3D sound effects. The museum illustrates the AKP mythology, which aims to instruct citizens in the way to interpret the history of the conquest, as well as the Byzantine ruins spread over and beneath contemporary Istanbul.

These are at least locations people can choose to visit, but daily riders on the metro are also compelled to travel to the glorious past, in the tiles of metro stations ranging from across Istanbul from Taksim to Kadıköy. In these and many other ways, the AKP has inscribed its own mythical, Disney Park narrative of Ottoman history onto the immense complexities of Istanbul. Here is where historians can intervene to disrupt the overly simplified, callous re-creation of Turkey’s past.

[The entrance to Taksim metro station. Image via Dani`s Logbook.]

In the same week as Erdoğan gave his speech at the archives, there was an ornate, symbol-laden ceremony to announce that the third bridge in Istanbul would be named after Selim the Grim, an Ottoman sultan known for his gruesome suppression of the Alevi Turkmen population in Anatolia in the sixteenth century. Besides these projects, almost every day for the last four years, Turkish citizens have woken up with the news of how many children they should have in order to keep Turkey’s population growing, how hazardous smoking and drinking are for their health, and how Turkey’s economy is booming. Often, these things are personally declared by Erdoğan, who commonly uses an authoritarian tone and a first-person address; he refers to himself instead of his party in describing a policy or the result of policy, and uses possessive suffixes every time he refers to Turkish citizens. This is a discourse very similar to that used by the autocratic Sultan Abdülhamid II as he simultaneously opened thousands of new schools and censored the press so that graduates of these new schools could not publicly disagree with him. However, in Turkey, conservative and liberal Islamists were generally pleased by the growing political charisma of Erdoğan.

Before leaving Turkey for his visit to Tunisia, Morocco, and Algeria on 3 June, Erdoğan described the protesters as looters, a small minority of marginal characters, and extremists, while seriously understating the numbers of people involved. He later referred to them as Janissaries, alluding to the Janissaries’ practice of overturning their soup cauldrons and revolting against the Sultan when they wanted more pay or a different Sultan (a strategy that succeeded more often than not). It is telling that Erdoğan sees the protestors as Janissaries, since to many observers he seems to wish for precisely the kind of autocratic authority he imagines the Sultans to have had. In a recent interview with Habertürk , Erdoğan stated that redevelopment plan for Taksim Square would include not only building a mall, residence, or city museum and a mosque, but also clearing up the areas around the historic Hagia Triada Orthodox Church. Erdoğan said that these projects would illustrate a clear view of “our civilization,” which can be read in reference to the nostalgia for the co-existence of the Ottoman Empire. In truth, however, sultanic authority was always constrained by the forces of empire, including the inherent chaos of empire itself, which could be governed but not controlled.

This is but one of the lessons historians could teach Erdoğan: good governance is about managing the inherent chaos of human interaction, not about imposing ever tighter and more polarizing strictures of orderly control. Parliamentary democracy hinges on compromise and respect for the opposition that may someday take your place as leaders in a different coalition. Ottomanalgia, whatever its creators may have intended it to be, has all too easily been turned by Erdoğan into permission for his authoritarian “I have decided” rhetoric. If historians and other scholars speak with courage and scholarly impartiality, with allegiance to truth rather than to Ottomanalgia, then the explosive tensions between the government and a large percentage of Turkish citizens over the future of Taksim Square can push us re-think power, space, and memory. We must take that debate out of the hands of politicians and put it into free discussion among people with an allegiance to truth, not to pernicious fictions.